- By James Gallagher

- Health and Science Correspondent

4 minutes ago

Photo credit, Katie Ewer

A malaria vaccine with “world-changing” potential has been developed by scientists at the University of Oxford.

The team expects it to be rolled out next year following trials showed up to 80% protection once morest the deadly disease.

Basically, the scientists say, their vaccine is cheap and they already have an agreement to manufacture over 100 million doses per year.

The charity Malaria No More has said recent progress means children dying of malaria might disappear “within our lifetimes”.

It has taken more than a century to develop effective vaccines because the malaria parasite, which is spread by mosquitoes, is spectacularly complex and elusive. It is a constantly moving target, changing shape inside the body, making it difficult to immunize once morest it.

Last year, the World Health Organization gave the historic green light for the first vaccine – developed by pharmaceutical giant GSK – to be used in Africa.

However, the Oxford team say their approach is more efficient and can be manufactured on a much larger scale.

Results of trials involving 409 children in Nanoro, Burkina Faso have been published in the Lancet Infectious Diseases. It shows that three initial doses followed by a booster one year later give up to 80% protection.

Photo credit, Katie Ewer

Trials took place in Burkina Faso

“We believe these data are the best data to date from the field with any malaria vaccine,” said Professor Adrian Hill, director of the university’s Jenner Institute.

The team will begin the approval process for its vaccine in the coming weeks, but a final decision will depend on the results of a larger trial of 4,800 children planned before the end of the year.

The world’s largest vaccine maker – the Serum Institute of India – is already poised to manufacture over 100 million doses a year.

Professor Hill said the vaccine – called R21 – might be made for “a few dollars” and “we might really see a very substantial reduction in this horrible burden of malaria”.

He added: “We hope this will be rolled out and available and life saving, certainly by the end of next year.”

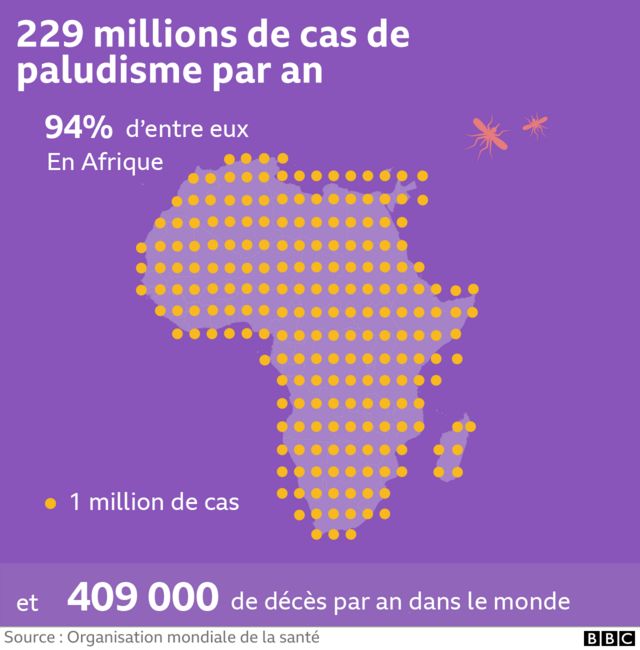

Malaria has been one of the greatest scourges of humanity for millennia and mainly kills babies and infants. The disease still kills more than 400,000 people a year even following dramatic advances in mosquito nets, insecticides and drugs.

There are 229 million cases of malaria per year in the world, 94% of which are in Africa.

This malaria vaccine is the 14th Professor Katie Ewer has worked on at Oxford because “it’s not like Covid where we have seven vaccines straight away that will work…it’s much, much more difficult”.

She told the BBC that it was “incredibly rewarding” to get this far and that “the potential fulfillment this vaccine might have if rolled out might really change the world”.

Why so effective?

The currently approved vaccine – made by GSK – shares similarities with the one being developed at Oxford.

Both target the first stage of the parasite’s life cycle by intercepting it before it reaches the liver and takes hold in the body.

The vaccines are constructed using a combination of malaria parasite and hepatitis B virus proteins, but the Oxford version contains a higher proportion of malaria proteins. The team believe this helps the immune system focus on malaria rather than hepatitis.

The success of the GSK vaccine has partly paved the way for Oxford to be optimistic regarding the release of its vaccine next year – for example by assessing the feasibility of a vaccination program in Africa.

It is difficult to directly compare the two vaccines. GSK has undergone extensive real-world trials, while Oxford data may appear more effective as it is provided just before the peak malaria season in Burkina Faso.

Professor Azra Ghani, chair of infectious disease epidemiology at Imperial College London, said the results of the trial were “very welcome”, but warned it would take money to get vaccines in arms.

“Without this investment, we risk losing the gains made over the past decades and seeing a growing wave of malaria resurgence,” Prof Ghani said.

Gareth Jenkins, from the charity Malaria No More UK, said: “The current results of the R21 vaccine from the renowned Jenner Institute in Oxford are another encouraging signal that with the right support, the world might end deaths children due to malaria in our lifetime.”