The artist is famous. It’s even entered popular culture, inspiring the saga’s dread emoticon and horror mask. Scream At the movie theater. And yet…” Of Munch we often know only The Scream, declares Claire Bernardi, director of the Musée de l’Orangerie and curator of the exhibition presented at the Musée d’Orsay. After the “Munch and France” exhibition (Musée d’Orsay, 1991), following “Edvard Munch. The modern eye” (Centre Pompidou, 2011), the time had therefore come to devote a real retrospective to Edvard Munch (1853-1944), embracing a career spanning sixty years. Organized by the Orsay and Orangerie museums, with the exceptional assistance of the Munch museum in Oslo, the artist’s legatee, the exhibition brings together some sixty paintings as well as a significant set of drawings and prints. . As for pronunciation, « Mounk » is becoming widespread, despite resistance from « Munk » among some Norwegian purists…

living things that breathe

« He is an artist who has disappeared behind a work. His name is familiar without being, we don’t know how to pronounce it. Where does it come from, what century does it belong to? His work is abundant, powerful, of great coherence. We are seduced or not, but we are carried away by his universe. Son of a doctor living in Christiania (now Oslo), Munch cut his teeth painting portraits of his family and friends. Marked by an austere realism, his works became clearer under the influence of Impressionism, whose touch he also adopted, as evidenced by evening time from 1888 (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza). After a first stay in Paris in 1885, Munch settled there from 1889 to 1892. But it was in Berlin, where he caused a sensation in 1892 with a major exhibition of fifty-five of his works, that he began to write. the major chapter of his long career. After a feverish period of travel, the artist settled in Norway in 1908.

Edvard Munch, Evening Hour, 1888, oil on canvas, 75×100.5 cm, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid ©Munch Museum / Munch-Ellingsen Group / VEGAP

Distancing himself from Impressionism, Munch declares in his Manifest from 1889: “We will no longer paint interiors with men reading and women knitting. We want to paint living beings, who breathe, feel, suffer and love. […]. I am going to do a series of paintings in this spirit; it will be necessary that we understand what is sacred in them, and that people uncover themselves before them as if they were in a church. » Death lurks around The sick childscandal at the Salon d’AutomneOslo in 1886. The work is inspired by the tragic fate of his sister Sophie, defeated like their mother by tuberculosis. Love, loneliness and death now weave the fabric of a work marked by a pessimistic vision of human destiny. ” First centered on his loved ones, his family, his intimate universe, his work is rooted in European symbolism, comments Claire Bernardi. Character of the bohemian Christiania, the poet and theoretician Hans Jaeger, whom he painted in 1889, evokes this irruption of intimacy in art, the importance of the feeling of self in artistic or literary expression. His portrait marks the culmination of Munch’s first manner. It neighbors in the exhibition with theSelf-portrait with a cigarettean attempt at introspection emerging from the blue darkness.

Edvard Munch, L’enfant Malade (The Sick Child), 1896, huile sur toile 121.5 x 118.5 cmh Gothenburg Museum of Art, Suède © Gothenburg Museum of Art. Photo : Hossein Sehatlou

A poem of life, love and death

With Despairwhose red sky and composition prefigure The Screamwith Pubertyevoking the difficult transition to adulthood, The sick child forms the beginning of a story that will become the central theme of Munch’s work, the frieze of life, tirelessly recomposed until the 1930s and 1940s. ” The frieze is designed as a series of paintings of the same nature which, forming a whole, will give an image of life, writes the artist. The interminable line of the shore, behind which the eternally moving sea foams, runs through the frieze from end to end; under the trees breathes multiple life with its sorrows and its joys. The frieze is felt as a poem of life, love and death.»

Edvard Munch, Girls on the Bridge, 1927, 100.5 × 90 cm, Oslo, Norway, Munchmuseet Photo: CC BY 4.0 ©Munch Museet

These last words form the subtitle of the exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay which, rather than a chronological party, adopts a cyclical approach which makes it possible to integrate into the story paintings painted on dates very distant from each other. Declining certain themes obsessively, the painter gives many versions of his key works. Thus The sick child knows six versions, the last dated 1927; Vampire or Young Girls on the Bridge experience the same fortune. ” As Gauguin and the great artists of the end of the 19th century, founders of a certain modernity, he thinks of his work as a wholecontinues Claire Bernardi. He constantly reworks the same motif without ever doing the same thing once more, moves it into another universe, until the 1930s. He digs, explores different techniques, his pictorial technique itself evolves a lot. »

Edvard Munch, Vampire, 1895, oil on canvas, 91 × 109 cm, Oslo, Norway, Munch Museum Photo : © CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Munch Museum

The sun is rising

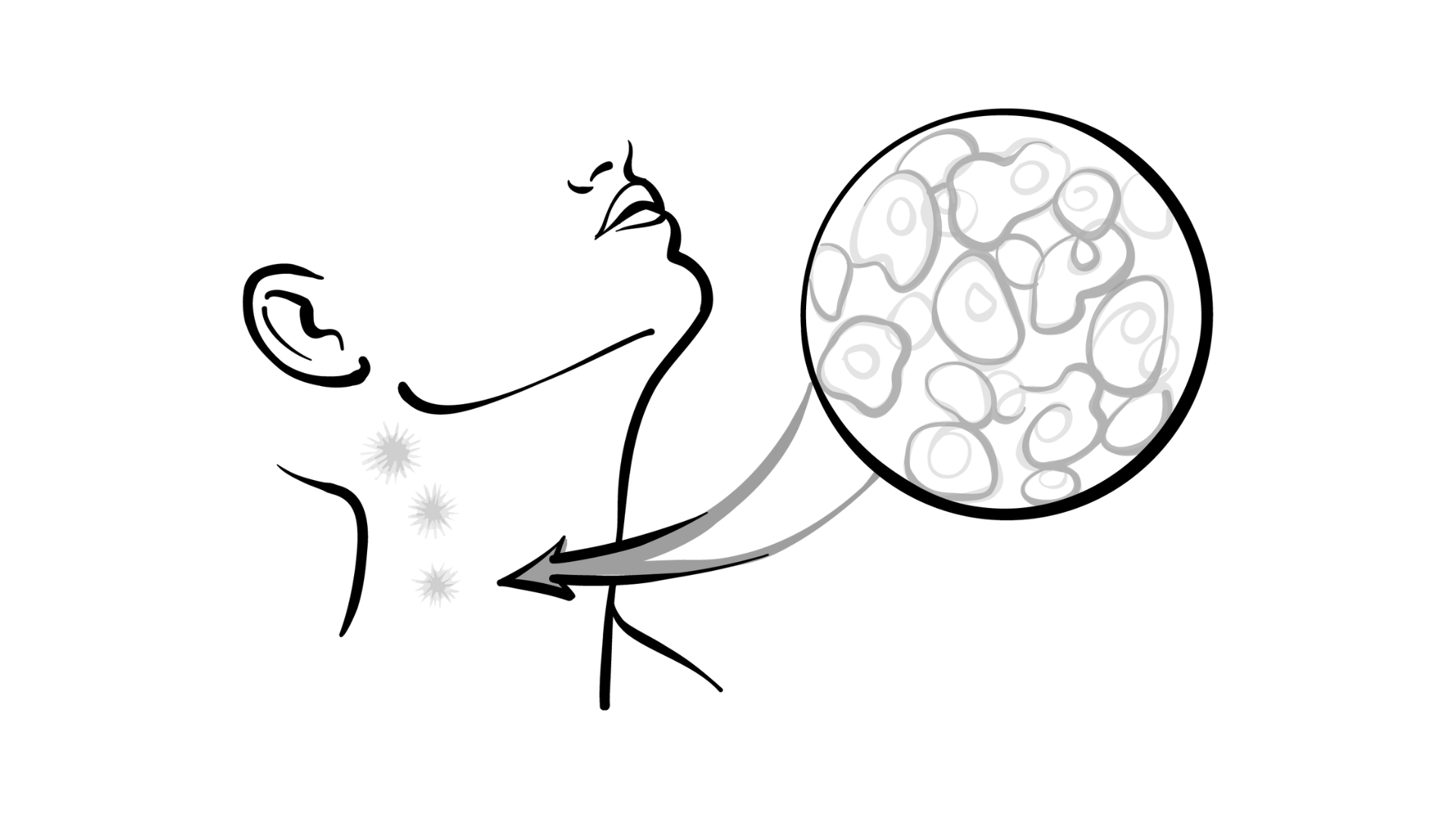

The print, of which Munch is, like Gauguin, one of the undisputed masters, herself plays a major role in the deepening of her pictorial language. Pivotal work of the frieze of life, Metabolism (1898-99, Oslo, Munch Museum) illustrates the biological process of the perpetual cycle of life. Depicted on the frame, the roots of the tree feed on decomposed corpses. Another flagship work of the frieze, Madone is available in several versions. In the lithograph, the frame evokes this same cycle of life: a cadaverous-looking fetus accompanies the representation of this woman transfigured by carnal ecstasy, while spermatozoa snake around the frame. Obsessed with death, Munch never ceases to sing regarding life, even in its microscopic manifestations!

Edvard Munch, ,Madonna, 1895-1896, lithograph printed in black, hand-coloured with red, blue and yellow, The Gundersen Collection, Oslo, Norway Photo: The Gundersen Collection/Morten Henden Aamot

Close to avant-garde theater circles, the artist created sets for the Théâtre de l’Œuvre in Paris and for Max Reinhardt in Berlin. In return, the works of Ibsen or Strindberg inspire his huis clos (Jealousy, 1907) and even some self-portraits where he identifies with a character in the drama. After his voluntary confinement in a psychiatric hospital for serious nervous disorders in 1908, he discovered the joys of nudism on the beach while convalescing in Warnemünd. Under the influence of Nietzsche and the vitalist current, the sun rises and color is released in large canvases painted in the open air.

Edvard Munch, Le soleil, 1912, huile sur toile, 123 × 176.5 cm, Oslo, Norway, Munch Museum Photo ©: CC BY 4.0 Munch Museum

Symbol of knowledge enlightening men but also of the rebirth of Norway, which has become independent, The sun which he places at the center of his monumental decoration for the aula of the University of Oslo is the symbol of this renewal. In the 1940s, the artist let pure color vibrate in his last self-portraits. Far from the gloomy Symbolist camera, the master who inspired the German Expressionists fixes his pathetic old age in the burning colors of summer.