(CNN) — The red supergiant Betelgeuse, a colossal star in the Orion constellation, experienced a massive stellar eruption the likes of which had never been seen before, according to astronomers.

Betelgeuse first came to attention in late 2019 when the star, which shines like a red gem on Orion’s upper right shoulder, underwent an unexpected dimming. The supergiant continued to dim in 2020.

Some scientists speculated that the star would explode as a supernova, and have since tried to determine what happened.

Now, astronomers have analyzed data from the Hubble Space Telescope and other observatories, and believe the star underwent a titanic surface mass ejection, losing a substantial portion of its visible surface.

“We’ve never seen such a huge mass ejection from the surface of a star before. We find that something is happening that we don’t fully understand,” said Andrea Dupree, an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard and Smithsonian in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a statement.

“It’s a totally new phenomenon that we can directly observe and resolve surface details with Hubble. We’re looking at stellar evolution in real time.”

Our sun regularly experiences coronal mass ejections in which the star releases parts of its outer atmosphere, known as the corona. If this space weather reaches Earth, it may have an impact on satellite communications and power grids.

But the surface mass ejection that Betelgeuse experienced released more than 400 billion times more mass than a typical coronal mass ejection from the sun.

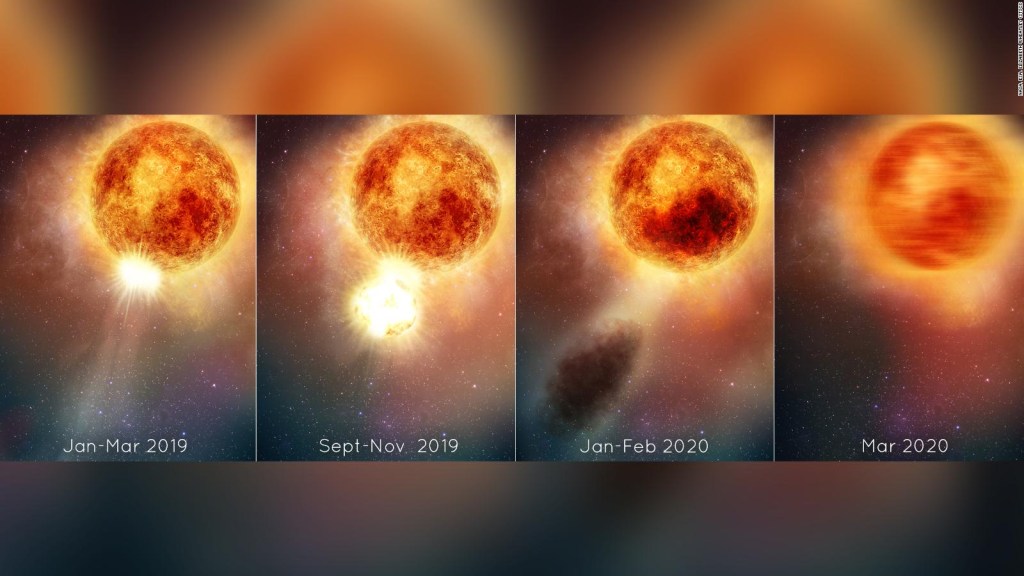

This illustration shows the eruption that caused the red supergiant star Betelgeuse to mysteriously darken.

the life of a star

The observation of Betelgeuse and its unusual behavior has allowed astronomers to observe what happens at the end of a star’s life.

As Betelgeuse burns the fuel in its core, it has grown to massive proportions, becoming a red supergiant. The massive star is 1.6 billion kilometers in diameter.

Ultimately, the star will explode as a supernova, an event that might be briefly visible during the day on Earth. Meanwhile, the star is experiencing some intense outbursts.

The amount of mass that stars lose at the end of their lives when they burn up through nuclear fusion can affect their survival, but even the loss of a significant amount of their surface mass is not a sign that Betelgeuse is ready to explode. according to astronomers.

Astronomers like Dupree have studied how the star behaved before, during and following the eruption in an effort to understand what happened.

Scientists believe that a convective flow, more than 1.6 million kilometers in diameter, originated in the interior of the star. The flow created shocks and pulsations that triggered an eruption, shedding a chunk of the star’s outer shell called the photosphere.

The chunk of Betelgeuse’s photosphere, weighing several times more than the Moon, was released into space. As it cooled, the mass formed a large dust cloud that blocked out the star’s light, noticeable when viewed through telescopes on Earth.

Betelgeuse is one of the brightest stars in Earth’s night sky, so its dimming, which lasted a few months, was noticeable in both observatories and backyard telescopes.

blast recovery

Astronomers have measured Betelgeuse’s rhythm for 200 years. The pulse of this star is essentially a cycle of dimming and brightening that restarts every 400 days. That pulse has ceased for now, a testament to how consequential the eruption was.

Dupree believes that the convection cells inside the star that drive the pulsation are still reverberating from the explosion, comparing it to the splash of an unbalanced washing machine tub.

Telescope data have shown that the star’s outer shell has returned to normal as Betelgeuse slowly recovers, but its surface remains elastic as the photosphere rebuilds.

“Betelgeuse is still doing very unusual things right now,” Dupree said. “The interior is like bouncing.”

Astronomers had never seen a star lose so much visible surface, suggesting that surface mass ejections and coronal mass ejections might be two very different things.

The researchers will have more opportunities to observe the mass ejected from the star using the James Webb Space Telescopewhich might reveal additional clues through infrared light, which would otherwise be invisible.