(CNN) — Yale University researchers say they have been able to restore blood circulation and other cellular functions in pigs within an hour of the animals’ death, suggesting that the cells are not dying as quickly as scientists had assumed.

With more research, the cutting-edge technique might one day help preserve human organs longer, allowing more people to receive transplants.

The researchers used a system they developed called OrganEx that allows oxygen to be recirculated throughout the body of a dead pig, preserving cells and some organs following cardiac arrest.

“These cells are working hours later than they should,” said Dr. Nenad Sestan, the Harvey and Kate Cushing Professor of Neuroscience and Professor of Comparative Medicine, Genetics and Psychiatry at Yale, who led the study.

“And what this tells us is that you can stop cell death. And restore functionality to multiple vital organs. Even an hour following death,” he told a news conference.

the scientific magazine Nature published the research this Wednesday.

“This is a truly remarkable and incredibly significant study. It shows that following death, cells in mammalian (including human) organs, such as the brain, do not die for many hours. This is until well into the postmortem period.” -mortem,” Dr. Sam Parnia, associate professor of critical care medicine and director of critical care and resuscitation research at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, told the Science Media Center in London. Parnia was not involved in the research.

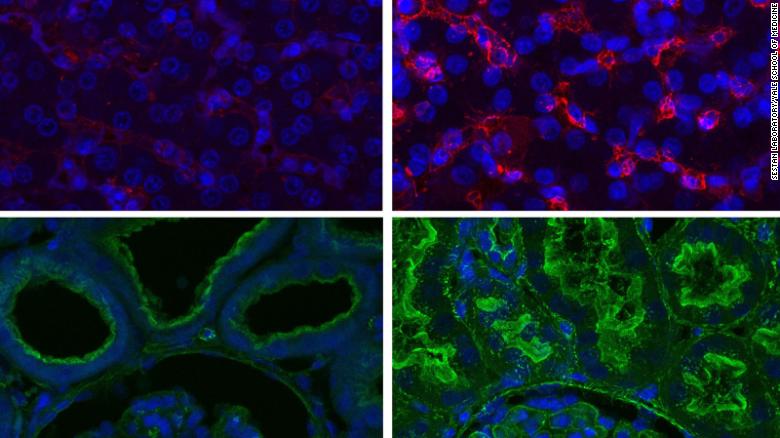

The top images represent the liver and the bottom images represent the kidney. Cells on the left have been perfused control, while images on the right represent organs perfused with the OrganEx system detailed in the new study. They show the integrity of the tissue and that certain cellular functions have been restored.

The OrganEx system pumps a fluid called perfusate, mixed with blood, through the blood vessels of dead pigs. Perfusate contains a synthetic form of the protein hemoglobin and several other compounds and molecules that help protect cells and prevent blood clots. Six hours following the OrganEx treatment, the team found that certain key cellular functions were active in many areas of the pigs’ bodies, including the heart, liver and kidneys, and that some organ function had been restored.

It builds on research published by the same team in 2019 that used a similar experimental system called BrainEx that delivered artificial blood to the brains of pigs, preventing the degradation of important neuronal functions.

How might the research be applied to humans?

While the research is still extremely early and highly experimental, the researchers said they hoped their work in pigs might eventually be applied to humans, primarily in terms of developing ways to extend the window for transplants. The current supply of organs is extremely limited, leaving millions of people around the world waiting for transplants.

“I think the technology holds great promise for our ability to preserve organs following they are removed from a donor,” co-author Stephen Latham, director of the Yale Interdisciplinary Center for Bioethics, said at the briefing.

“You might take the organ from a deceased donor and connect it to this technology, and then maybe be able to transport it long distances over a long period of time to get it to a recipient in need.”

The researchers made it clear that they were by no means bringing the pigs back to life and that more work would be needed to understand whether the organs were usable for transplants.

“We cannot say that this study showed that any of the organs of this pig were … ready to be transplanted into another animal, we do not know if they are all working, what we are seeing is at the cellular and metabolic levels,” Latham explained. “And we’re nowhere near being able to say, ‘Oh my gosh, we’ve brought not only this pig back to life, but any of the individual organs.’ We can’t say that yet. It’s still too early.”

The research has the potential to lead to new treatment strategies for people experiencing a heart attack or stroke, said Robert J. Porte, MD, of University Medical Center Groningen, in the Netherlands, in an article published along with the studio.

“One might imagine that the OrganEx system (or components of it) might be used to treat such people in an emergency. However, it should be noted that more research will first be needed to confirm the safety of system components in specific clinical situations.” “said Porte, who was not involved in the investigation.

However, Latham said that possibility was “pretty remote.”

“This idea of connecting (a) person who had an ischemic injury, you know, someone who drowned or had a heart attack, I think is pretty far off. The much more promising short-term potential use here is with preservation of organs for transplantation.

The researchers used up to 100 pigs as part of the study, and the animals were under anesthesia when the heart attack was induced.

The research also helps scientists better understand the process of death, something that is relatively understudied, Sestan said.

“Within a few minutes following the heart stops beating, there’s a whole cascade of biochemical events triggered by the lack of blood flow, which is ischemia. And that leads to the shutdown of oxygen and nutrients that cells need to survive. And this starts to destroy the cells,” Sestan added.

“What we show … is that this progression toward massive permanent cell failure doesn’t happen so fast that it can’t be prevented or possibly corrected.”