- Valentina Oropeza Colmenares – @orovalenti

- BBC News World

2 hours

image source, Getty Images

Many parents make the dangerous journey with their children through the Darien.

As soon as he examined the patient, Dr. José Antonio Suárez warned that in a few hours there would be dozens of people with the same symptoms.

The rash spread over the patient’s legs and feet. The skin was inflamed and red. The more she scratched, the more it itched.

It was the 2:00 in the followingnoon and the doctors were intrigued. What was the cause of that dermatitis? If Dr. Suárez’s prognosis came true, how might they deal with a massive contagion in the middle of the Darien jungle?

“The patient was a Venezuelan man who had crossed the border between Colombia and Panama on foot,” says Suárez, a 67-year-old Venezuelan infectologist and pediatrician, specializing in Tropical Medicine.

Those injuries were similar to those that assaulted the specialist when he was a teenager and visited the hospital with his father. laguna de unarein the eastern Venezuelan plains.

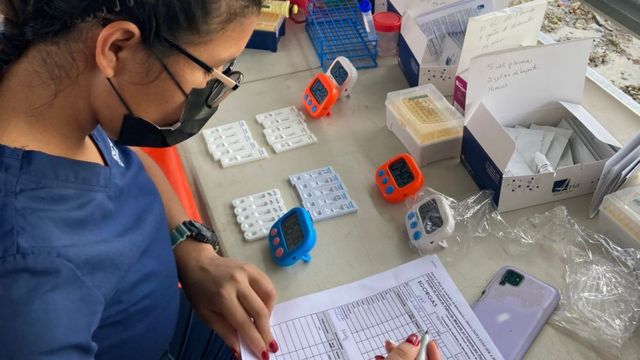

image source, Physicians of the Gorgas Institute of Panama

Doctor José Antonio Suárez treats a patient in the Darién.

While studying medicine in Caracas, he found out that the eruption was caused by cercarias, larvae of parasites that usually lodge in river snails and other water sources. However, they die upon entering a person’s tissue because they stray into the skin, the largest organ in the human body.

At 7:00 at nightMore than 20 people scratched their legs as they lined up to be seen by the clinical team at the Gorgas Commemorative Institute for Health Studies in Panama.

The eruption was called dermatitis cercarial. The challenge was to discover how the migrants from Darien had become infected.

image source, Physicians of the Gorgas Institute of Panama

A patient in Darien with cercarial dermatitis.

The impact of death

In January 2022, Suárez and a group of Latin American doctors organized a 9-day operation in San Vicente, a migrant reception center where Panamanian authorities register and assist those who manage to reach the northern Dariena dense jungle of more than 575,000 hectares, which lacks highways and delimited paths that allow orientation in transit between Panama and Colombia.

This humid tropical forest, located east of Panama, is a natural barrier between Central and South America that is also known as the Darien Gap.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimates that 133.000 personas crossed the Darien region during 2021. The majority were Haitians, Cubans, and Venezuelans, followed by citizens from countries as far afield as Bangladesh, Ghana, Uzbekistan, and Senegal.

This year, the IOM has reported the increase in migrants from Venezuelawhich is going through an economic, political and social crisis that has driven the exodus of more than 6 million people since 2015, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency.

Of some 500 people who attended during the operation, 70 were interviewed in depth by the doctors.

“What most impacts migrants is seeing killed by jungle or violence“says Suarez.

While videos circulate on social networks of migrants who say they have lost their relatives during the journey, the IOM reported that last year at least 51 people died or disappeared in the Darien.

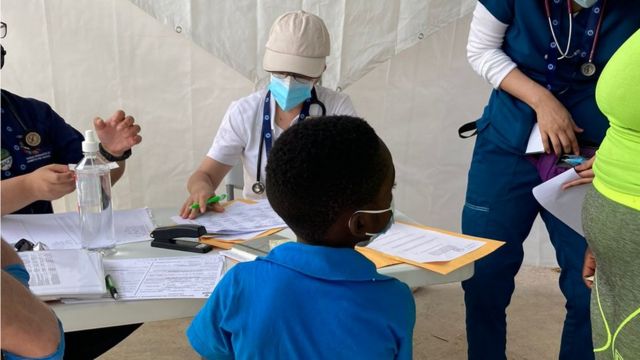

image source, Physicians of the Gorgas Institute of Panama

Most of the patients treated were Haitians, Venezuelans and Cubans.

Jump into the void

In front of the small wooden house where a service for sending remittances and selling chips and mobile phones operates in San Vicente, doctors from the Gorgas Institute set up tents to shelter four query stations: one for General and Tropical Medicine, one for Mental Health, another for Reproductive Health, and the last one for Nutrition.

Suárez treated a 60-year-old Venezuelan man who was traveling with two children, 4 and 5 years old. Although he found no resemblance between them, he assumed they were his grandchildren.

The man clarified that they were the children of a Haitian woman he had met in the jungle. He gave them to her so that she might take them to San Vicente because he no longer had the strength to walk.

“The degree of desperation is such that a father can release a son with a stranger to take him to the middle of the jungle,” says Suárez.

image source, Physicians of the Gorgas Institute of Panama

The specialists installed a mobile laboratory to process samples from patients in the Darién.

At the same station of the operation, the Panamanian epidemiologist Roderick Chen-Camaño received a Venezuelan patient who burst into tears when questioned to fill out the medical history.

He said that he was climbing a mountain with a group of migrants when the mother of a Haitian family collapsed. Upon verifying that she had died, her husband took one of her two children and threw him off the cliff. The Venezuelan boy struggled with him to prevent him from doing the same with the other, but he was unsuccessful. After throwing his two children, the man jumped into the void.

Although he has previously worked in the jungle with indigenous communities, Chen-Camaño says he left the Darién physically and mentally exhausted.

“I thought I was prepared, that I would not see anything new. But it was a completely new experience. I have three children and I see their faces in every child that walks through that place.

image source, Physicians of the Gorgas Institute of Panama

The doctors attended to some 500 patients during a week in the operation in the Darién.

Delight’s Luck

Panamanian biologist Yamilka Díaz was in charge of processing blood and urine samples taken by doctors to diagnose malaria, dengue, chikungunya, hepatitis, syphilis, Chagas disease and HIV.

Delicia was the reason Diaz had joined that operation. She was a 5-year-old girl who came to the Gorgas Institute to be treated, following a man found her next to the corpse of his mother in the middle of the Darien jungle.

When the biologist asks her if she remembers anything, Delicia replies that his family was taken by the river.

Diaz left San Vicente without shoes. He donated them to a 60-year-old Venezuelan whose feet were infected by a fungus that lodged in the fabric of his feet.

If he continued to walk around in those shoes, he would continue to get infected.

“Going to the Darién and being with the migrants changes your life. You see everything differently. One can complain that gasoline is expensive or problems at work, but there you see people who really have a subsistence problem“.

image source, Physicians of the Gorgas Institute of Panama

Migrants arrive with injured feet at care posts in the Darién due to the long walks.

children without names

Venezuelan pediatrician Laura Naranjo, wife of Dr. Suárez, received a woman who showed her her Venezuelan passport to fill out the medical history. The doctor told her that she was lucky to have that document, difficult to process in Venezuela.

“Doctor, you don’t know what I had to do to keep this passport,” replied the woman, holding back tears. She later told that she had been abused in the jungle.

Panamanian internist and infectologist José Anel González treated a woman who confessed to having been raped on the way through the Darién. Although she knew that she had HIV, she did not tell her aggressors.

image source, Getty Images

Migrants face extreme conditions in the jungle.

“Many are victims of robberies and rapes in the jungle, although nobody counts who commits these crimes. Migrants just want to get to the United States,” adds Dr. Suárez.

The first of the five nights they slept in San Vicente, Panamanian pediatrician Yesenia Williams Alvarado was unable to leave her room to talk to her colleagues regarding what they saw that day.

The children came so dehydrated that their mucous membranes were sunken and they cried without tears. Some were so disoriented that they mightn’t remember their names.

“There were nameless children who were born on the journey. others came alone. Everyone had a lost look. They have witnessed things they shouldn’t experience,” says Williams.

“I did not expect so much suffering or so many difficulties. It is very frustrating to know that that operation was just a palliative. We only see a small part of what they are experiencing.”

image source, Physicians of the Gorgas Institute of Panama

Doctors treated children traveling alone who mightn’t remember their names.

The danger of the rivers

While examining the children, Panamanian pediatrician Rosela Obando realized that none had rashes like the adults. The parents explained that they carried them during the journey to avoid the risk of being swept away by the currents of the rivers.

The doctors discovered then that the migrants were infected in the rivers, where the feces contaminated with cercariae of the migratory birds that pass through the Darién, one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in Central America.

Migrants also drink from them, so Suárez assumed that many would have gastritis and lesions due to ingestion of cercariae. Those who avoid doing so to prevent diarrhea run the risk of dying of dehydration.

“It is a avian cercarial dermatitis in humans that had never been reported in this area,” explains Suárez.

image source, Getty Images

The rivers of the Darien are contaminated with cercariae.

The specialist is concerned can not to follow to these patients, who only spend a few days in San Vicente. Then they take a bus to the border with Costa Rica, to continue on their way to the United States.

“This disease in humans produces liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and cancer“, details.

A decade ago, Suárez left the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Caracas to emigrate to Panama. The operations in the Darién offer him an opportunity to help other Venezuelans.

“This experience in the Darién marked my life. I felt dismayed and grateful to God. I emigrated by plane and with financial support, while these people have nothing.”

Now you can receive notifications from BBC World. Download the new version of our app and activate it so you don’t miss out on our best content.