Why would anyone join an institution that forbids family life and requires celibacy?

Ultimately, reproduction is at the very heart of our own evolution. However, many religious institutions around the world require the Vow of chastity.

The practice led anthropologists to wonder how celibacy might have evolved in the first place.

Some suggested that practices that have a high cost to people, such as never having children, can arise when people blindly conform to norms that benefit one groupsince cooperation is another cornerstone of human evolution.

Others argued that people create religious (or other) institutions because they serve their own selfish or family interests and reject those who do not get involved.

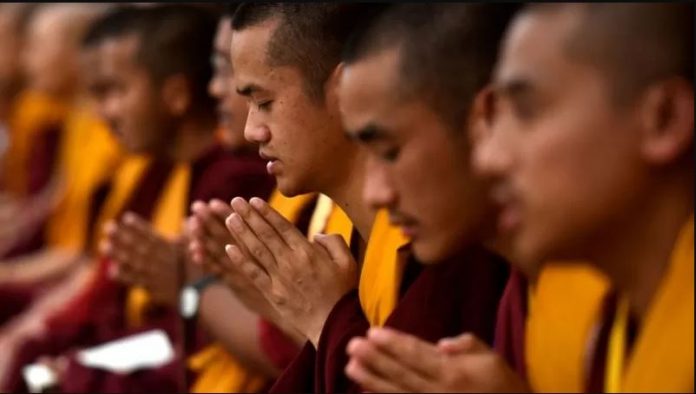

Now a new study, published in the Royal Society Proceedings B and conducted in western China, addresses this fundamental question by studying the lifelong religious celibacy in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries.

Until recently, it was common for some Tibetan families send one of their young children to the local monastery to become a celibate monk for life.

Historically, as many as one in seven boys became a monk. Families often cite religious reasons for having a monk in the family. But Were there also economic and reproductive considerations?

Patriarchal family structure

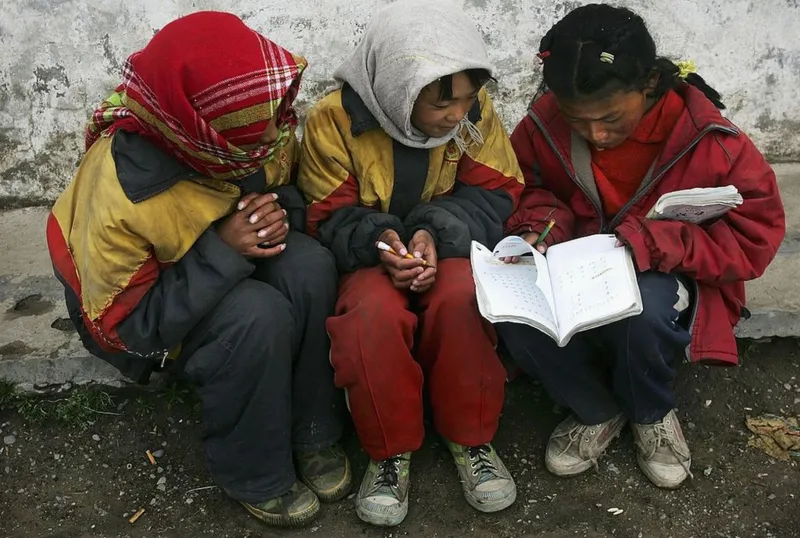

In collaboration with Lanzhou University in China, 530 households in 21 villages in the eastern part of the Tibetan Plateau in Gansu province were interviewed.

Family genealogies were reconstructed, gathering information regarding each person’s family history and whether any of their relatives were monks.

These towns are inhabited by Amdo Patriarchal Tibetans who raise goats and yaks (a kind of long-haired domesticated cattle) and farm small plots of land. Generally wealth is passed down from father to son in these communities.

Men with a monk brother were richer and they owned more yaks. But there was little or no benefit to the sisters of the monks. This is likely due to siblings competing for the parent’s resources, land and livestock.

Since monks cannot own property, by sending one of their sons to the monastery, the parents put an end to this fraternal conflict. Firstborn sons generally inherit the parental house, while monks are usually second or third sons.

Surprisingly, men with a monk brother had more children than men with non-celibate brothers, and their wives had children at a younger age.

Grandparents with a monk son also had more grandchildren since their non-celibate sons had little or no competition with their siblings.

The practice of sending a child to the monastery, far from being costly for the parents, would be in line with the reproductive interests of the parents.

Mathematical model of celibacy

This suggests that celibacy may evolve by natural selection.

To know more details, a mathematical model of the evolution of celibacy was built, where the consequences of becoming a monk in the evolutionary development of a man, his brothers and other members of the community were studied.

A direct consequence of the existence of monks is that there are fewer men competing to marry women in the village.

But while all the men in the village might benefit if one of them becomes a monk, the monk’s decision does not favor his own evolution. Therefore, celibacy should not prosper.

However, that situation changes if having a brother who is a monk makes men richer and therefore more competitive in the marriage market.

Now religious celibacy can evolve by natural selection because, while the monk is not having children, he is helping his brothers to have more.

It is important to note that if the choice to become a monk rests with the child himself, then it is a rare act. From the perspective of an individual, it is not very advantageous.

In the model, celibacy becomes much more common only if it is the parents who decide what should happen in their children’s lives.

Parents benefit from all their children, so they will send one to the monastery whenever there is an advantage for the others.

The fact that boys were sent to the monastery at a young age with much celebration and then faced disgrace if they later abandoned their role suggests a cultural practice shaped by parental interests.

This model might also shed light on the evolution of other types of parental favoritism in other cultural contexts, including infanticide.

And a similar framework might explain why celibate women (nuns) are rare in patriarchal societies like Tibet, but might be more common in societies where women compete more with each other, for example, where they have more inheritance rights (as in parts of Europe).

It is often argued that the spread of new ideas, even irrational ones, can result in the creation of new institutions as people adjust to a new standard.

But it may be that institutions can also be shaped by people’s reproductive and economic decisions.

*Ruth Mace is Professor of Anthropologyia from UCL and Alberto Micheletti is a researcher at UCL.

This note was originally published on The Conversation