- Louis Fajardo

- BBC Monitoring

1 hour

image source, Getty Images

This Sunday Colombia witnessed the strangest election in its entire history.

In a country that for decades had been described as the most conservative in the hemisphere, a majority of regarding 70% of voters disillusioned with the the status quo they gave not one, but two withering blows to an electoral tradition who had spent two centuries electing a representative from “the same as always”.

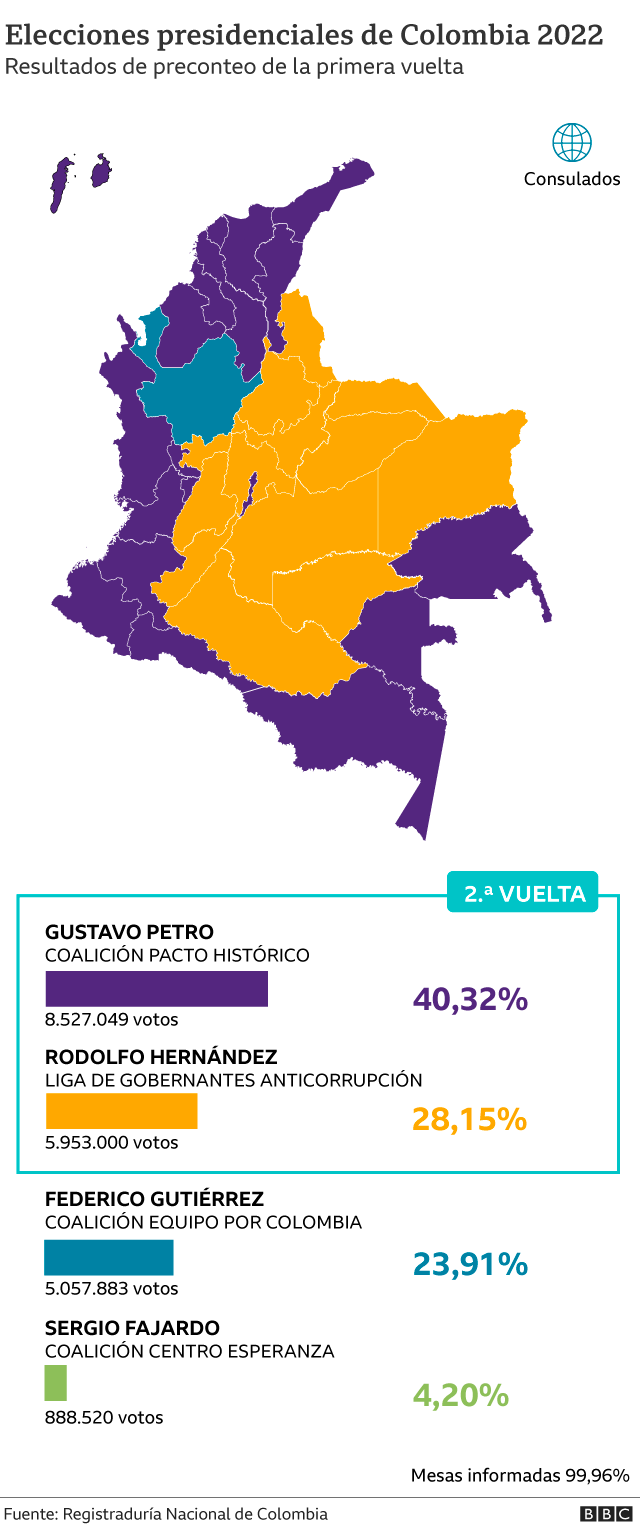

What is predicted as a very disputed second round of the elections on June 19 will face Gustavo Petro and Rodolfo Hernandezwhose projects have excited the majority of voters in the first round.

They don’t have much in common, except that they are the tangible manifestation of an “anti-system” vote, rejecting many traditional bastions of Colombian politics.

A country that since the time of Simón Bolívar and the wars of independence boasted of preferring moderate conservatism to extremes in politics, voted this Sunday for a leftist leader who promises a radical economic democratization of the country.

And on the other from the right that anticipates a deep purification of the corruption that, in his opinion, corrodes Colombian democracy.

The great sacrifice of the day, of course, is Federico “Fico” Gutierrezthe candidate of the right-wing coalition Team for Colombia, the representative of the “establishment” and the country’s traditional politics, who came in third place this Sunday, out of the race to determine the next president.

For this situation to happen in Colombia, very long-term trends that had been eating away at the stability of the traditional political system coincided this Sunday with other more immediate ones that precipitated its collapse.

There were also global trends with others of a very local nature. Everything converged to unleash the electoral hurricane experienced this Sunday.

image source, Getty Images

The role of the pandemic

In the first place, the Colombian institutions designed from the 1991 Constitution have had the explicit objective of incorporating social, ethnic and ideological diversity into the political life of the country.

the same Gustavo Petro He came to politics following the leftist guerrilla to which he belonged, the M-19, signed a peace agreement with the Colombian State 32 years ago, almost at the same time that one of the most guaranteed constitutions in the region was proclaimed.

Since then, year following year, many taboos have been broken that restricted political participation and diversity in Colombia.

Petro bets as a running mate for the vice presidency by Francia Márquez, a woman, black and an environmental activist.

There were also very strong global economic currents that shook the country’s stability, creating the right situation for a rejection of the the status quo. To go no further, the pandemic created an economic crisis in 2020 and 2021 that left millions in poverty or at the doorstep.

“The pandemic created one of the worst employment crises in Colombia in more than a century,” Colombian professor and labor economics expert Juan Carlos Guataqui told BBC Mundo.

image source, Getty Images

Gustavo Petro shares the presidential ticket with Francia Márquez.

But then, was this collapse of the Colombian political tradition that was observed on Sunday inevitable? Many would say no. In addition to global and long-term factors, there were also local and circumstantial reactions that determined the collapse.

The wear and tear of President Duque and the protests

With its scant public support, the erosion of the government of the current Colombian president Ivan Duke“with very few results to show”, helped accelerate the discrediting of the prevailing order and “accelerated the consolidation of these independent movements”, I assure BBC Mundo Monica Pachonpolitical scientist and professor at the Universidad de los Andes.

The political mistake made by the then Minister of Finance, Alberto Carrasquilla, of promoting at the beginning of 2021 a tax reform that threatened more taxes on a population submerged in the disgrace of the pandemic helped trigger the national strike April of that year, the most violent protests the country experienced in almost half a century.

At the same time, the death of dozens of civilians in confrontations with the security forces during that national strike they contributed to many saying that they would not vote “for the usual ones” once more.

In Cali, the city that was the epicenter of these disturbances, the results of the recent parliamentary elections in March showed strong correlations between the neighborhoods where the most violence was observed and the level of voting in favor of the opposition led by Petro.

“The results of the congressional elections show that Gustavo Petro [y su partido] They were finally the ones that got the most electoral revenue from the 2021 strike once morest the government of Iván Duque,” the Colombian news portal La Silla Vacía said in a tweet on April 22.

image source, Getty

There was also the failure in the current presidential campaign of several moderate centrist candidates such as Sergio Fajardo, Ingrid Betancur and Alejandro Gaviriawhich in the midst of constant disputes between them failed to show the voter a coherent and credible alternative.

On the night of the election, Fajardo told the press in his country: “It was clear that Colombia wants to change.” But he was never able to convince Colombia that this change was happening through him or through his moderate colleagues.

The fall of uribismo and the networks

And of course in the center of the ruler’s defeat uribista movement there is the apparent political decline of its maximum leader, former president Alvaro Uribe. After two decades of being the personification of his country’s conservative establishment, the former president spent this electoral cycle in relative discretion and few believe that he is the most powerful political figure in the country.

Neither of these situations was inevitable. By occurring all at once, they accelerated the Colombian transition to a more polarized politicsevidenced in the electoral results of this May 29.

One last factor helped make Sunday’s electoral romp possible: the emergence of social networks as a determining factor in political communication in the country.

For decades, many of the traditional Colombian media prided themselves on being guardians and protectors of the institutional order. Today they have been displaced in political relevance by social networks, where many of their influencers are far from having a similar commitment to tradition.

As Colombian journalist and political analyst María Elvira Duzán told the BBC last April: “It is the first time in Colombia that we are seeing such an impact in terms of social media. [en las elecciones]”.

The journalist then indicated the ability of Petro and Hernández to mobilize the electorate using platforms such as TikTok.

Ironically, it was Uribismo and the current governing party, the Democratic Center, which a few years ago gave the first great lesson in the political usefulness that these social networks might have during their fierce opposition to the peace process with the FARC and the government. who supported him, that of the then president Juan Manuel Santos.

When I was in opposition Uribism was very effective in transmitting, via social networks, a feeling of indignation around the doubts and fears generated by the peace process.

In 2016, shortly following the majority of Colombians voted NO in a referendum on the peace process with the guerrillas, which was opposed by former President Uribe, one of the leaders of his movement, Juan Carlos Vélez, confessed to the newspapers Colombians the effective strategy of the messages he sent through social networks: “We were looking for people to go out and vote, boar [expresión coloquial colombiana para indicar “furiosa” o “enardecida”]”.

image source, Twitter Andres Pastrana

In Colombia, the political wing that had controlled the government for decades, such as former presidents Uribe, Pastrana and Gaviria, is called “the usual ones.”

Six years later, in 2022, the places were changed. The opposition led by Petro and Hernández was the one that caused that feeling of indignation once morest the ruling party and “the usual ones” to spread through social networks.

Rodolfo Hernández, lifesaver of the status quo?

For many in the Colombian ruling class there is no doubt that in the situation created following the May 29 election Rodolfo Hernandez he is the candidate who promises to save them from the radical left that his critics attribute to Petro.

This Sunday the first electoral bulletins announcing his advantage over Fico Gutiérrez had not finished being issued when many “establishment” figures sided with Hernandez.

In a tweet, the congresswoman and former presidential candidate for the Uribista Democratic Center party, María Fernanda Cabal, announced: “The country needs changes, not the suicide that Petro offers, but authority, order and the prosperity offered by a businessman like the engineer Rodolfo Hernandez”.

But it is not clear that this candidate, a man of humble origins who has built his image by calling the traditional political class corrupt, is ready to become an instrument of it.

image source, Archyde.com

Rodolfo Hernández was a little-known businessman until he launched his presidential campaign.

“Hernandez, by not participating in the coalitions [de partidos políticos tradicionales en el actual proceso electoral], showed that he was not interested in participating in that policy. They invited him to those coalitions and he said no,” Mónica Pachón tells BBC Mundo.

Although, as Pachón recalls, if Hernández ends up winning the presidency, will not have a single legislator formally representing it in the Cnational ongress. Therefore, it will be difficult for him to govern without some form of support from that traditional ruling class that today proclaims him as the last lifesaver in the midst of the spectacular shipwreck of the Colombian leadership.

Whatever the outcome of next June 19, in Colombia the balance of power has just changed.

The oldest ruling class in the hemisphere, the same one that has survived the centuries in that South American nation, will now have to adjust to a different and inevitably diminished role.

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC World. Download the new version of our app and activate it so you don’t miss out on our best content.